|

| Coelophora inaequalis by N. Bay (permission obtained) |

Table of Contents

Ladybirds are like the Audrey Hepburn of the insect world – classy, pretty and iconic (in my opinion). These tiny creatures were probably one of the pretty insects that you adored in your youth during one’s bug-catching phase. If that bug-lovin’ phase hasn’t died out for you or you’re simply bored at home on the internet, here’s a page that provides you with all the basic information you need to broaden your ladybird knowledge horizons!

While it comes with numerous names like ladybugs or ladybirds, this insect is neither bug (usually referring to another group of insects known as True Bugs. For more information on the differences between True Bugs and beetles, check out this website) nor bird. The more accurate name should hence be ladybeetle! Ladybirds aren't just charismatic and pretty, they can be voracious predators, and feed on pest insects that damage crops. Although most people’s impression of ladybirds is that of the classic red and black spottiness, the approximately 6000 described species have a diverse range of patterns and colours[1] . In fact, only 26 out of Britain’s 47 species exhibit the traditional black-on-red spots[2] . The 35 species of ladybirds found in Singapore all have a varying range of patterns too[3] !

What's in a name?

The name ‘ladybird’ was used in England for 600 years, mainly to refer to the common European beetle Coccinella septempunctata, also known as the Seven-spot Ladybird. However as more related species were described, this name has now been extended to all ladybird relatives under the order Coccinellidae. In the United States, ‘ladybird’ was Americanized to ‘ladybug’, and this has admittedly given rise to its varying, mildly confusing names[4] . |

| (1) Image of the Seven Spot Ladybird, by H. Macdonald, Mendip Wildlife from Flickr (permission obtained) |

Incidentally, the name coccinellid was derived from the latin word coccineus, meaning ‘scarlet’, and while we can agree these insects are not bird nor bug, they are definitely (at least the majority) red[5] .

Ladybird Mary

Ladybirds are named after a particular Lady, one we know as the Virgin Mary. Supposedly the name arose due to the red cloak the Virgin Mary is often depicted wearing in biblical paintings, similar to the red elytra (or hardened forewings) in the beetles[6] . Another story would be that in the Middle Ages, farmers were suffering from pest insects that ravaged their crops. After praying, help arrived in the form of these beetles, which the farmers referred to as 'Our Lady's beetles'[7] . |

| (2) Jan van Eyck’s Lucca Madonna in 1436, depicting the Virgin Mary, also known as Madonna, with her child, Jesus. Image obtained from Wikimedia Commons (Creative Commons) |

Additionally, people used to believe that the seven spots on Coccinella septempunctata parallel the seven graces and sorrows of the Virgin Mary[8] .Coelophora inaequalis, however, holds the common name of the Variable Ladybird, and the Latin name 'inaequalis' translates to irregular, or variable[9] . If you wish to find out more about the reason behind this species’ common name, do scroll down to this section!

How to Identify?

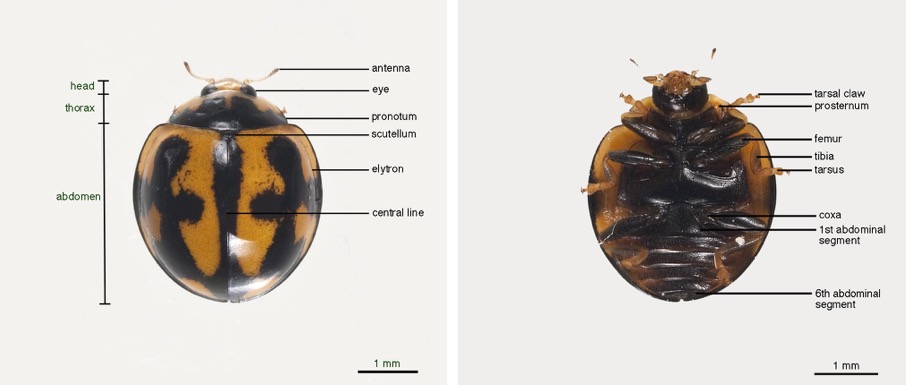

This species is small, roughly 4 – 7.5mm, with an oval hemispherical body, and convex glabrous (smooth, without pits) elytra. It has 11-segmented antenna ending in a small club, and its head is slightly withdrawn into the prothorax (first segment of the thorax)[10] . They can be distinguished from closely related species in the same genus by the absence of an infundibulum (a structure in the female genitalia)[11] . Below is an anatomical diagram. |

| (3) Dorsal and ventral view of Coelophora inaequalis. Images obtained from NZFactSheets (permission pending), annotations by Ashley Tan |

Why are the patterns variable?

|

| (4) Comic by D. Coverly, Go Comics (permission pending) |

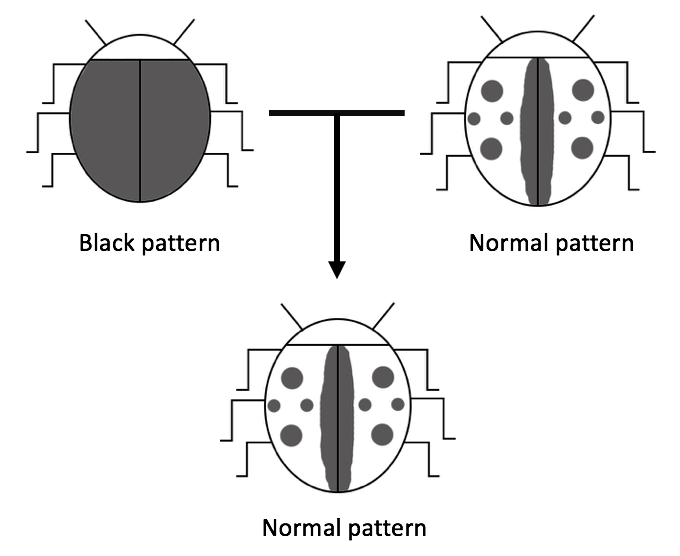

The species’ base colours range from orange to red. However its elytral patterns, as opposed to the usual spots, are highly variable, hence its name. Here’s the reason why our little friend is so hard to identify at first glance. Warning: this may get SLIGHTLY technical. The marked variation in colour pattern between individuals in the same species is actually known as polymorphism. As seen in the image below, patterns can range from stripes to spots to blotches, however the spotted and fused patterns are the most common.

|

| (5) Coelophora inaequalis and its identity crisis. This is all one species! Image from Ozwildlife (permission pending) |

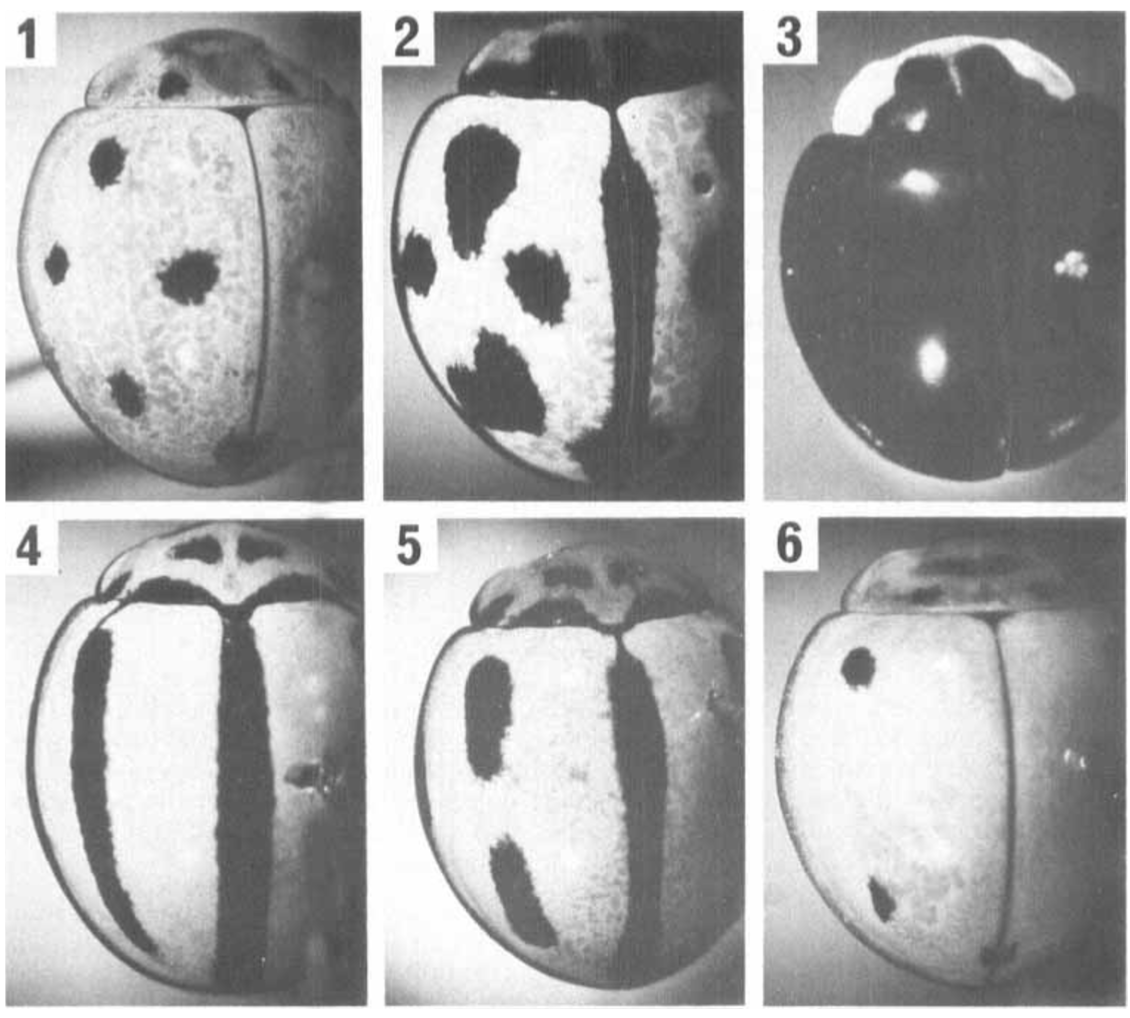

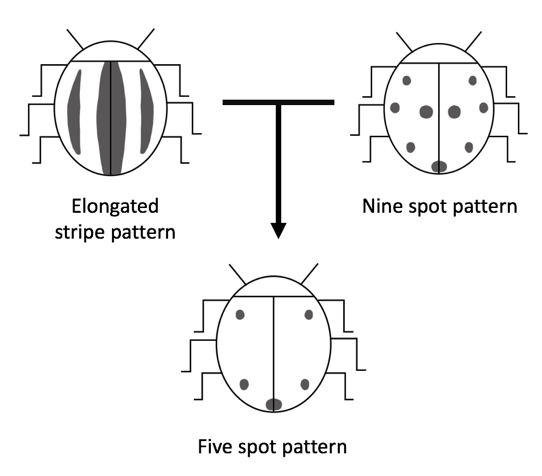

The inheritance of the various colour forms in the C. inaequalis has been studied several times, and it has been shown that these colour forms, or phenotypic variations, are controlled by multiple alleles in a single gene. To test the inheritance of these colour patterns, breeding studies were carried out by Houston in 1979, where different phenotypes (shown in the image below) were crossed to observe what kind of colour patterns the offspring would display. Results show that the appearance of these patterns is regulated by a principle called mosaic dominance, whereby black pigment in the elytra of a heterozygote offspring (an individual with two different types of a certain gene) will only form where there is black pigment in the elytra of both homozygous parents (where the parents have two copies of the same type of a certain gene)[12] .

|

| (6) The six colour forms that appeared in Houston’s study of mosaic dominance in 1979 (Fair use) |

Houston had two main takeaways:

1. If the black pigmented area of one homozygous parent is contained within the black pigmented area of the other parent, then the offspring will have a colour pattern the same as the parent with the smaller area of black pigment.

|

| (7) |

2. If the black pigmented area of one homozygous parent overlaps with or is not contained within the black pigmented area of the other parent, then the offspring will have a completely different colour pattern from both parents.

|

| (8) |

While the six colour forms seen in the previous image are the most basic ones, certain specimens do display slight differences such as fusion or reduction of the spots, as well as variations in the patterns on the pronotum. It is postulated that this could be due to the effect of environmental factors on the expression of the alleles regulating the insect’s colour patterns[13] . As of yet, however, no information has been found on whether or not these patterns influence the behavior, mating or predation of C. inaequalis.

Geographical Distribution

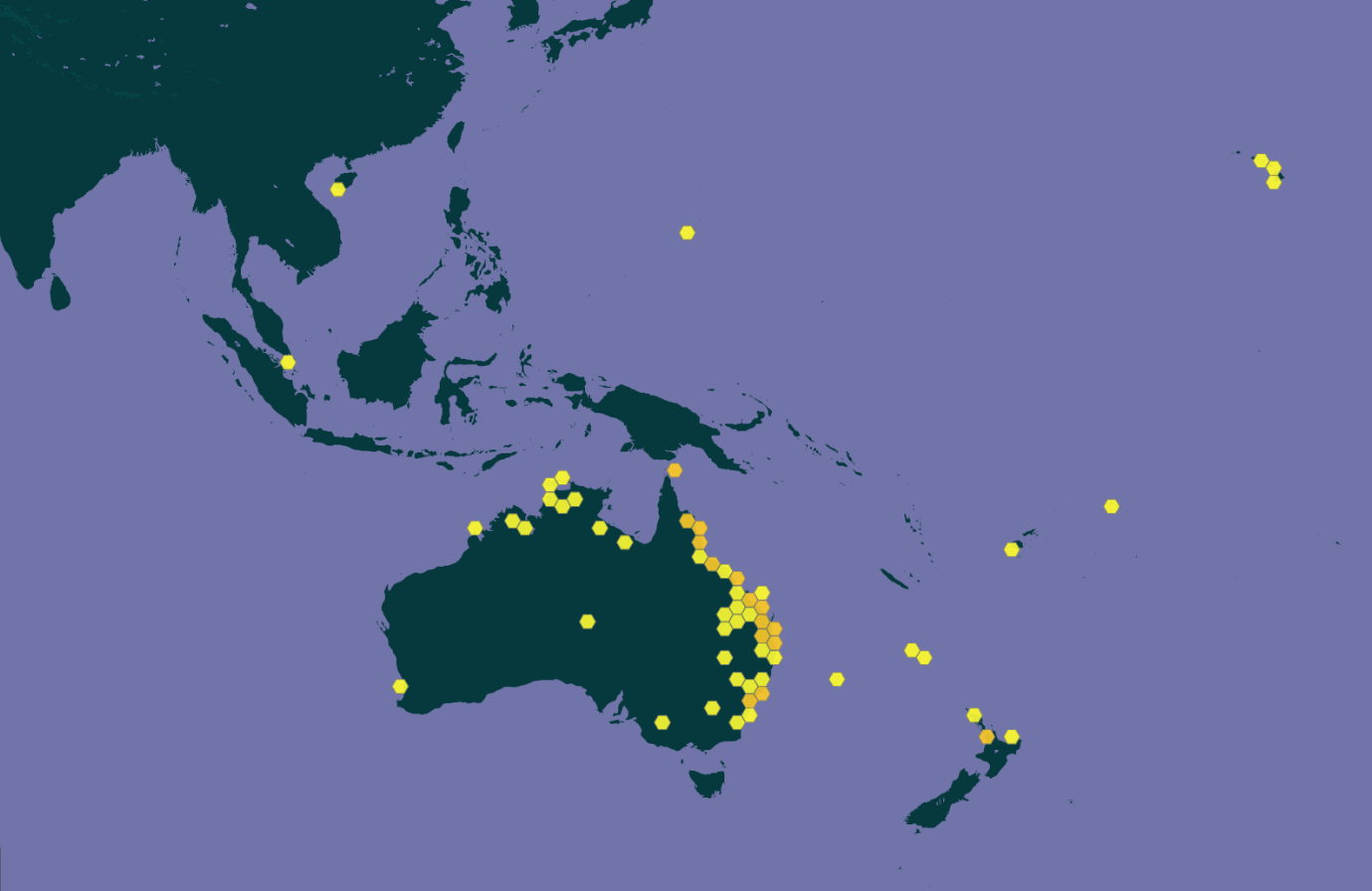

Coelophora inaequalis is mostly found in Southeast Asia and Australasia, as well as on the island of Hawaii[14] . For a closer look, check out the map here. Unfortunately, there doesn't seem to be any map made of the local distribution of C. inaequalis, nor a checklist of its sightings. If you've made any sightings of C. inaequalis, or any other ladybird, you can submit them here! |

| (9) Map of the global distribution of Coelophora inaequalis, taken from the Global Biodiversity Information Facility. Disclaimer: the actual species distribution may be more widespread than depicted |

Biology

Life Cycle

|

| (10) Life cycle of Coelophora inaequalis. Images obtained from NZFactsheets (permission pending), information obtained from BBC. |

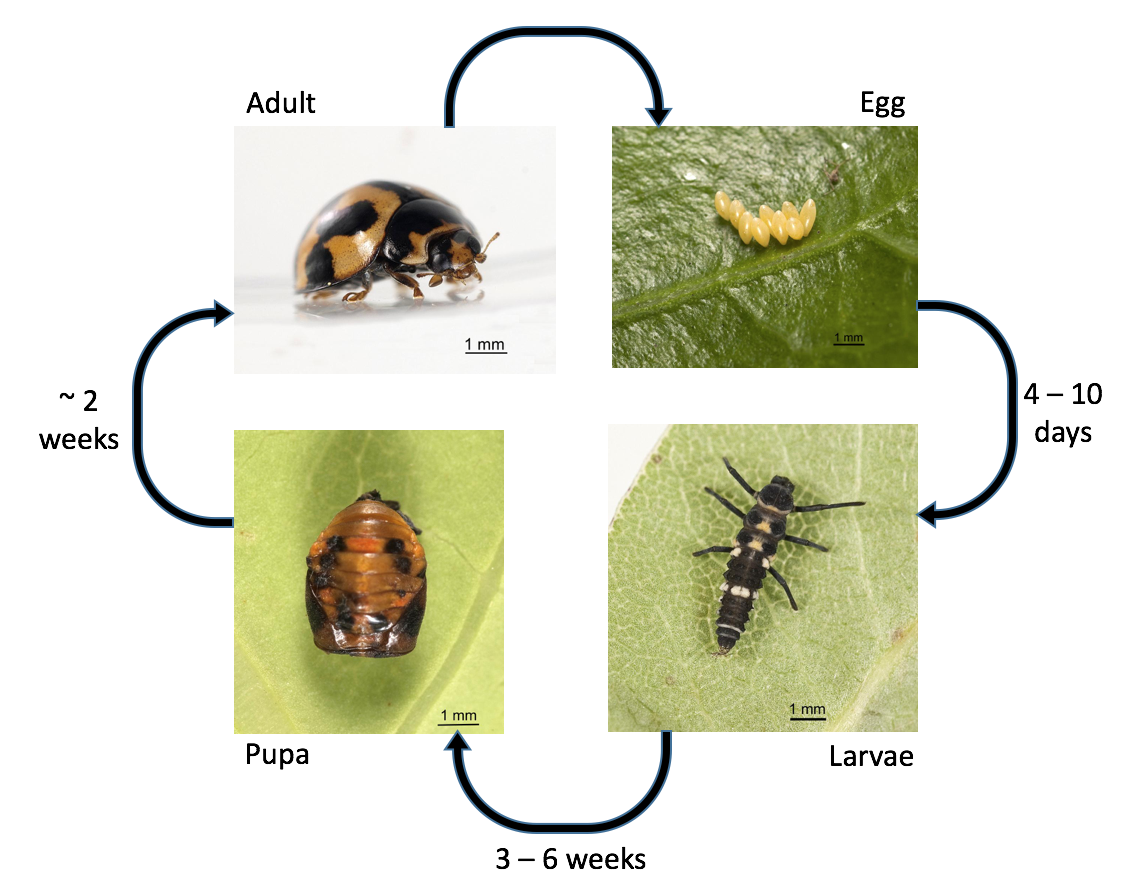

Coelophora inaequalis, as with all other beetles in the order Coleoptera, are holometabolous, meaning that the larvae will metamorphose into a completely different looking adult, with a resting stage known as a pupa. Eggs are laid on leaves, and the larvae that hatch are dark grey. The larvae go through four instars (stages) each time it moults. It moults into a pupa after the fourth instar and the colour varies from pale to mid-brown with black patches. Eventually, the adults emerge[15] [16] . The lifespan of C. inaequalis lasts for around 111-126 days[17] . For a brief and quick understanding of C. inaequalis' life cycle, look to the image above.

Habitat

Ladybirds are often found in a large variety of habitats such as forests, grasslands and even urban areas. Like most of its other relatives, Coelophora inaequalis can be found on shrubs and flowering plants in our local parks, gardens and forests, generally wherever aphids, its prey, are found[18] .Prey

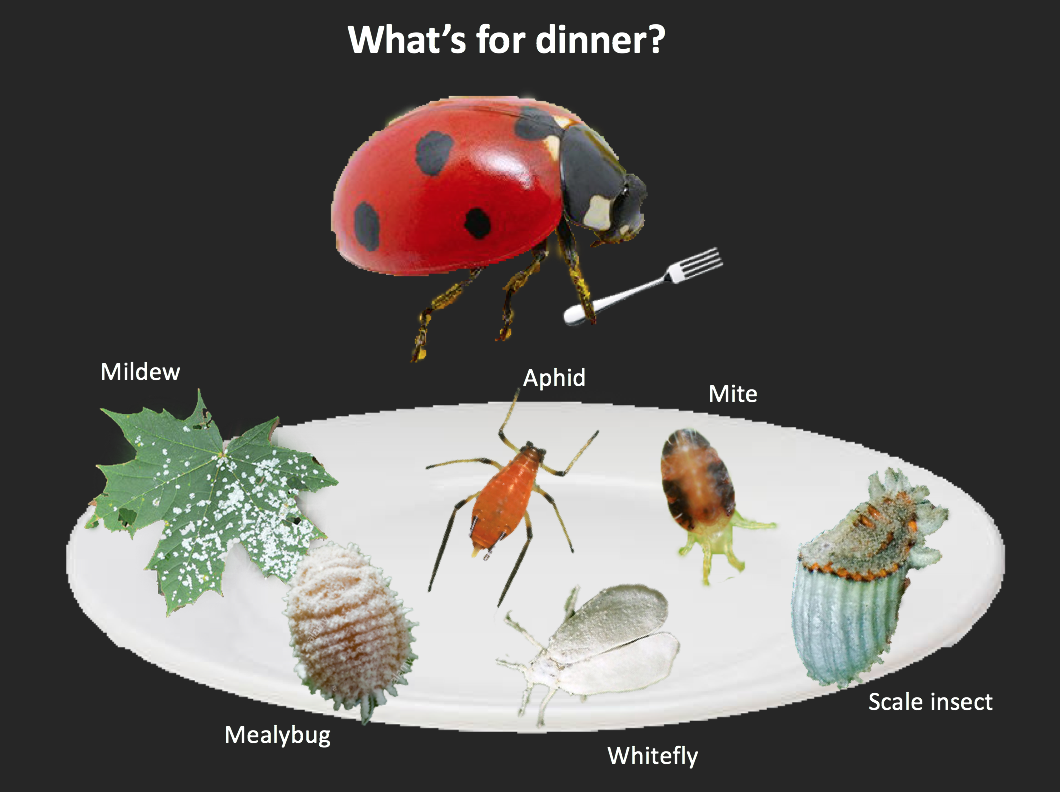

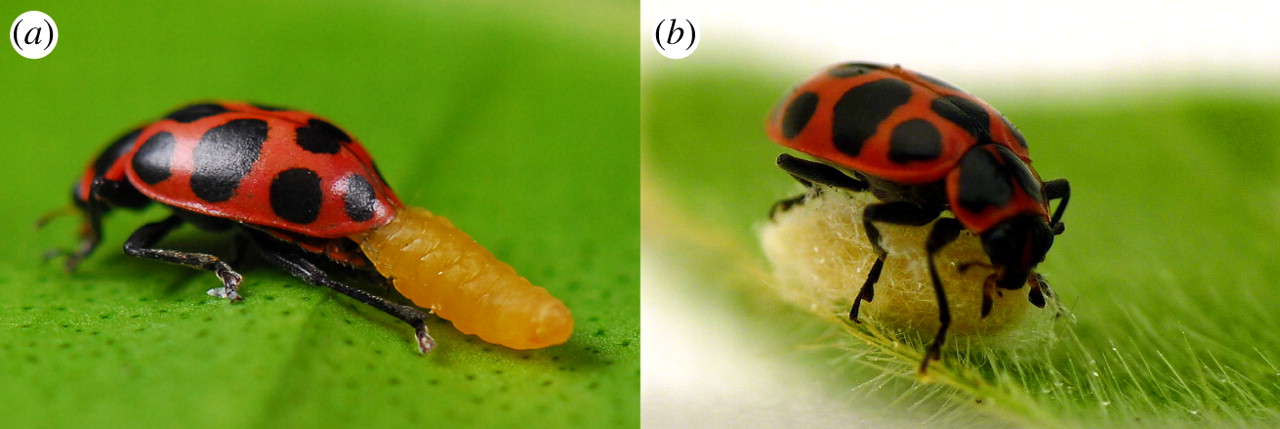

Coelophora inaequalis, like the majority of ladybirds, is predacious and feeds predominantly on aphids, another member of the True Bug family[19] . They have voracious appetites and are noted to feed on nine aphid species. However there are also records of it feeding on jumping plant lice (psyllids) and juvenile leafhoppers[20] [21] .For an extremely close up view of a ladybird and ladybird larvae munching on some aphids, scroll down to the video below!

Aside from being aphidophagous, Coccinellids are opportunistic predators and have a large range of diets. Some are herbivores and are crop pests, others feed on mildew, which are fungal growths on the leaves of plants. There are also species which feed on mites, scale insects or psyllids, the latter two of which belong to the order Hemiptera. They aren’t exactly picky eaters and during tough times of food scarcity, can turn to alternative food sources such as flower nectar, water and honeydew (which are secreted by sap-sucking bugs such as aphids and whiteflies)[22] .

|

| (11) Image of mildew, whitefly, scale insect, aphid, mealybug and mite from Wikimedia Commons (Creative commons) |

Coelophora inaequalis as biological control

A large part of the reason why Coelophora inaequalis and its kin are such charismatic critters and beloved by all is due to its beneficial diet on sap-sucking bugs, as mentioned above. Farmers look forward to the arrival of C. inaequalis, as it means a likely reduction in crop pests. Nearly a 100 out of the 4700 species in the aphid family are significant crop pests[23] , and these small insects can cause direct injury to crops and transmit plant viruses between individual plants.Aphids are host-specific, meaning one species of aphid only feeds and reproduces on one species of plant. They are a common pest in Singapore as well, and they devastate not just crops, but a whole range of other plants. Examples of these plants include legumes, hibiscus, pine trees and ornamental plants such as the oleander (Nerium oleander)[24] .

The effects of insecticide on aphids are also negligible due to the pests' ability to rapidly develop resistance.

|

| (12) Images of aphids clustered on a plant, from Wikimedia (Creative commons) |

This proclivity to non-insecticidal methods has led to the advent of ladybirds for biological control. Their bulldozer-like ability to chow down on any sap sucking bugs renders them an invaluable friend to farmers and gardeners, at practically zero cost (since these farmers no longer require expensive insecticides to get rid of pests). Additionally, not only do the adults feed on aphids, but the larvae as well. This proves highly advantageous as there need not be any delay in waiting for the larvae to pupate to adults in order to see an effect on the aphid population.

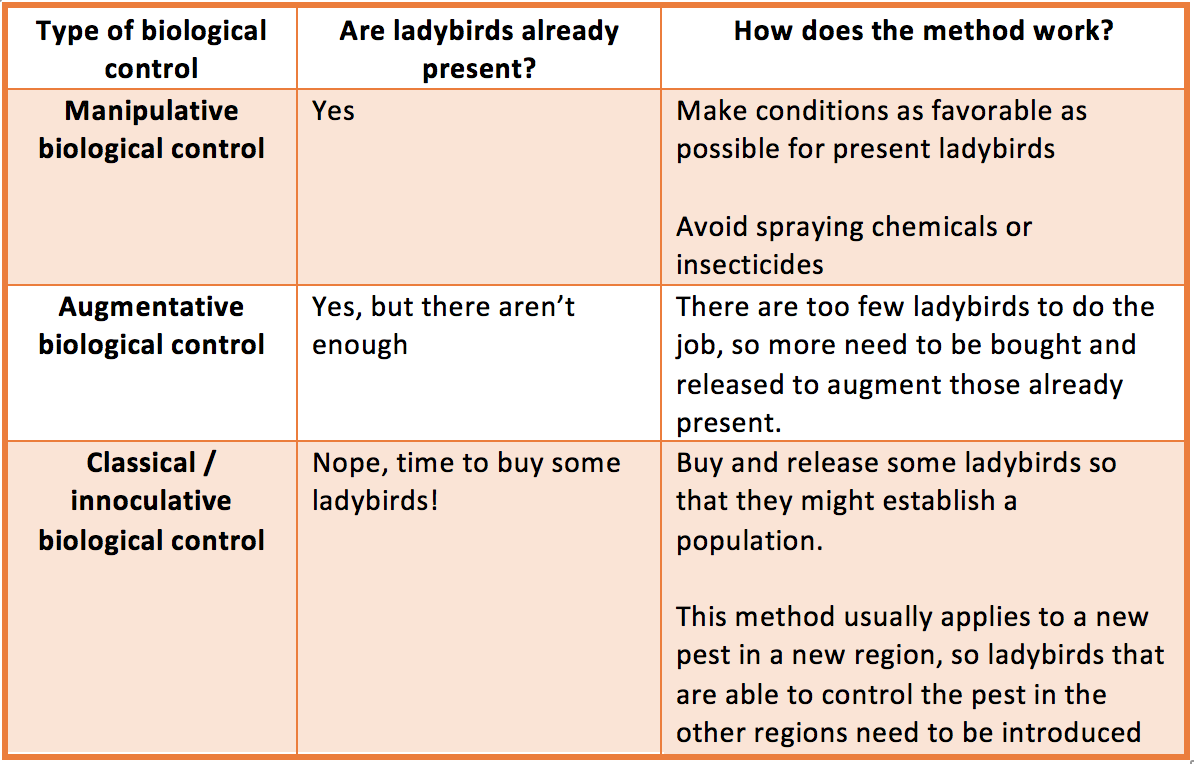

There exist three different methods of biological control, and these will be listed and elaborated on in greater detail in the table below.

Biological control using ladybirds does require extensive research beforehand, should ladybirds be introduced into an area just for this purpose. Ladybird populations may not establish, or if established, may not prey on the target pest species. Research on whether the particular ladybird species is effective in controlling the pest species in other regions is hence crucial to the success of such methods[25] . When research is properly done however, ladybirds are highly effective predators. Ladybirds have managed to reduce the aphid population by more than 50% in most studies[26] . Coelophora inaequalis was introduced into Hawaii from Ceylon and Australia to control aphids, and in the span of a decade, scientists remarked that they “were unable to find even a single specimen of a large black aphid”[27] . This species was also one of six species forming a species complex that managed to maintain aphid numbers below crop damaging levels in unsprayed cotton fields for three cotton seasons[28] .

Use of C. inaequalis in biological control should hence also entail proper education on the farmer’s part to ensure that none of their little friends would be unintentionally killed with insecticide, as the larvae are often mistaken for pests as well.

|

| (13) Coelophora inaequalis noms near its buffet spread. Image by Steve and Alison, Flickr (permission obtained) |

Behavior

Cannibalism

Timing is of the utmost importance when C. inaequalis does the dirty. Aphid colony numbers fluctuate highly, and there exists only a short window of time where C. inaequalis females, like all other aphidophagous ladybirds, can lay their eggs, in order for the larvae to mature in time before the aphids disappear[29] . |

| (14) Let’s Marvin Gaye and get it on ~ Image of Coelophora inaequalis mating by Budak (Creative Commons) |

Other than the timing, females also have to be fastidious in choosing a proper location to lay their eggs. Eggs are usually laid close to where aphid colonies are, so that once the larvae hatch they’re all ready to start chomping. However aphidophagous C. inaequalis mommas are usually reluctant to lay their eggs in areas already inhabited by other larvae. Why would this be a necessary precaution? This is where it starts to get morbid because C. inaequalis is actually a cannibal.

|

| (15) Image of C. inaequalis laying eggs, by N. Bay (permission pending) |

In times of famine i.e. low aphid abundances, C. inaequalis larvae will not hesitate to guzzle down their siblings, hatched or not. Furthermore, egg consumption is highly beneficial to the larvae’s growth and development[30] , making the potential for cannibalism even greater. Ladybird mommas hence do their best to avoid spots where larvae are already present, and they achieve this by detecting a specific pheromone released by the present larvae that deters oviposition (egg laying)[31] . Turns out that ladybirds aren’t even safe from… ladybirds.

|

| (16) Ladybirds should have been the poster child (pun not intended) for Hannibal Lecter in Silence of the Lambs instead. Image from Wikepedia (Fair Use), image of ladybird from NzFactsheets (permission pending) |

Natural Enemies

Ants

|

| (17) Ants and ladybirds decking it out?? Ant image from AntWeb (Fair Use), ladybird image by N. Bay (permission obtained), boxing image from Channel News Asia (permission pending) |

Coelophora inaequalis, like most aphidophagous (aphid-eating) ladybirds, possesses another common enemy – ants. In return for secretions of sweet honeydew rich in carbs and amino acids, ants actually protect the aphids from predators like the ladybird. The ants tend to the aphids almost as if they are sheep, and much like a farmer would cock his rifle to protect his livestock from a wolf, so would an ant ruthlessly defend its property.

|

| (18) Coelophora inaequalis facing off with an ant. Image by J. Thynne, Flickr (permission obtained) |

|

| (19) Another ladybird vs ant (with an aphid audience in the foreground). Image by B. Valentine (permission obtained) |

Aphid-tending ants tend to show greater aggression towards coccinellids near their tended colonies, and often times the level of aggression displayed towards enemies rises with their increasing proximity[32] . Occasionally, gladiator fights occur between the ladybird and several ant individuals. The softer-bodied larvae may be picked up and carried away by ants, dropped off the plant, or killed. Adults however, have greater defenses due to the harder carapace, and to protect their vulnerable ventral surface (underside) from strong ant mandibles, will drop one side of their body to make closer contact to the substrate and adhere more strongly to it[33] .

Parasitoids

|

| (20) Image of Dinocampus coccinellae, a common ladybird parasitoid, by T. Murray (Creative Commons) |

Aside from birds, C. inaequalis has few natural enemies. One parasitoid wasp, however, is particularly vicious. Dinocampus coccinellae, a Braconiid wasp, is cosmopolitan (meaning its found practically throughout the world) and targets a large number of coccinellid beetles, including C. inaequalis[34] . Instead of laying its eggs in hives or nests like other wasps, it chooses the path bordering on serial killer insanity. This wasp will lay its eggs in an unsuspecting individual, usually preferring larger instar larvae and adults, probably due to the greater nutrition they provide[35] . The wasp’s larvae then hatch WITHIN the ladybird, and proceeds to BURST OUT OF ITS BELLY. This is almost reminiscent of Scott Ridley’s Alien!

|

| (21) Image of Coelophora inaequalis couldn't be found so here's one of Dinocampus coccinellae larvae emerging from the abdomen of Coelomagilla maculata on the left, and the adult tending to the cocoon on the right. Images by Berkvens et al. (Fair Use) |

|

| (22) A gif of the chestburster from Alien in 1979. Similar to the ladybird no? |

Once the wasp larvae emerges from the individual, it spins itself into a cocoon. Interestingly, the C. inaequalis doesn’t flee, but remains paralyzed above the cocoon. Due to a type of RNA virus injected into the ladybird from the adult wasp in the very beginning, the ladybird has basically been transformed into a glorified zombie babysitter. Occasional twitches and small movements from it are enough to ward off predators looking to snack on the wasp pupa[36] .

Defense Mechanisms

Looking pretty and fending off enemies is all just in a day’s work for Coelophora inaequalis. Here are the various ways C. inaequalis, like almost all ladybirds, repel those unwanted harassers.

Chemical Defenses

Ladybirds are punk and they know it. Why else would they wear the colours red and black? That’s cos it spells DANGER, D-A-N-G-E-R. These colours act as a big fat warning sign to predators that this potential meal right here tastes nasty, and would spell not just danger, BUT REGRET. |

| (23) See this bright speck right here? This bright speck right here says NO. Image by E. Wee (permission pending) |

These contrasting patterns and colourations found on C. inaequalis’ elytra is also known as aposematic colouration. It mainly serves to broadcast to predators that the subject is unpalatable, toxic or nutritionally unprofitable[37] . What’s so toxic or unpalatable about it you may ask? When disturbed, C. inaequalis secretes a fluid, which isn’t pee, isn’t poo, its BLOOD. They literally bleed from their joints! The hemolymph (or ‘blood’) contains different alkaloids that give them their bitter taste and toxic properties, and this then oozes out through the joints in a defence mechanism known as reflex bleeding.

|

| (24) A ladybird (not Coelophora inaequalis), reflex bleeding orange hemolymph. Image by R. Ware (permission pending) |

Reflex bleeding however, is costly, and is only used as a last resort. This form of defence is costly in terms of the energy required in synthesizing the chemicals and in fluid loss, and hence is only employed when other strategies such as fleeing has failed. Additionally, larvae are more likely to reflex bleed than adults as their softer bodies puts them at greater risk to damage from predators[38] .

Behavioral Defenses

A smart ladybird knows when to cut its losses when fighting a losing battle. In such cases, C. inaequalis larvae often escape by running away or dropping to the ground, while adults may adopt these tactics or simply fly away. As mentioned previously under the section for Natural enemies, adult ladybirds may also clamp down on the substrate to protect their soft underbelly[39] .Physical Defenses

All good warriors wear armor and so do ladybirds. The adults’ tough exoskeleton and elytra make them relatively well protected against enemies. Larvae too, are protected by spiny protrusions (as seen below in C. inaequalis) or waxy coverings[40] . |

| (25) Larvae of Coelophora inaequalis and its spiky armor. Image by D. Lewin (permission obtained) |

Pop Culture

Folklore

Due to their voracious aphid-chomping ways, farmers welcome these tiny insects, and ladybirds have historically been known to represent symbols of good luck[41] . There is however, a darker side to its history, and its appearance in old nursery rhymes is proof of that. The rhyme goes like this –Ladybug ladybug fly away home, Your house is on fire, and your children are gone, All except one and that little Ann, For she crept under the frying pan.

As you recall, a ladybird’s name refers to Our Lady, the Virgin Mary, and here the ladybirds refer to Catholics or pagans who refused to participate in Protestant services in the olden days. Some Catholic priests were also burned at the stake. This took a rather morbid turn didn’t it[42] . To read more details about the rhyme, you can check out these websites here and here.

|

| (26) Image by L. Yannuci (permission obtained) |

Media Icons

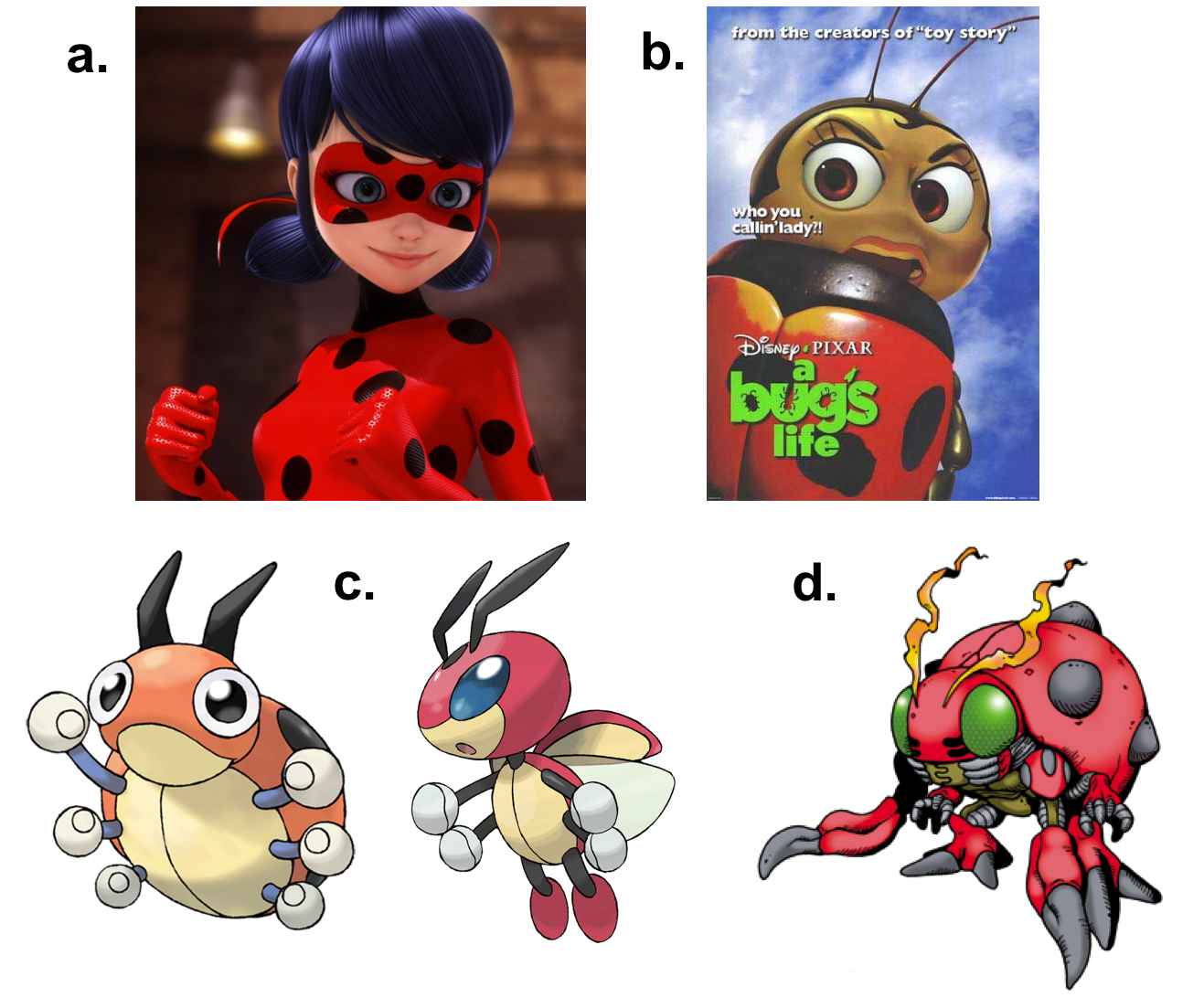

Ladybirds and their likeness have appeared several times in pop culture, and more often than not as more feminine characters in TV shows or movies. Below are a few examples. |

| (27) a. The female protagonist superheroine from the animated show Miraculous: Tales of Ladybug and Chat Noir, and her superpowers are even inspired by the traditional insect’s luck. Image from Wikia (Fair Use) b. “So, being a ladybug automatically makes me a girl! Is that it, flyboy?!” - Francis from Pixar's A Bug's Life, portrayed here in the movie poster. Image obtained from Wikia (Fair Use) c. Ledyba and Ledian from Pokemon. Images from Bulbapedia (Fair use) d. Tentomon from Digimon. Image from Wikia (Fair use) |

There are however occasions where the character defies conventional media or historical tropes. One of these is Francis, a ladybird from Pixar’s A Bug’s Life (pictured above in (b) ). The character is aggressive and short tempered, contrasting to the traditional gentle and graceful image of the ladybird. Even more ironically, Francis is a drag queen in the show[43] . Ladybirds have even appeared and inspired characters in popular series such as Pokemon and Digimon ( (c) and (d) ).

Taxonomy and Systematics

Classification

Kingdom Animalia Phylum Arthropoda Subphylum Hexapoda Class Insecta Order Coeloptera Suborder Polyphaga Superfamily Cucujoidea Family Coccinellidae Subfamily Coccinellinae Tribe Coccinellini Genus Coelophora Species Coelophora inaequalisType Specimen

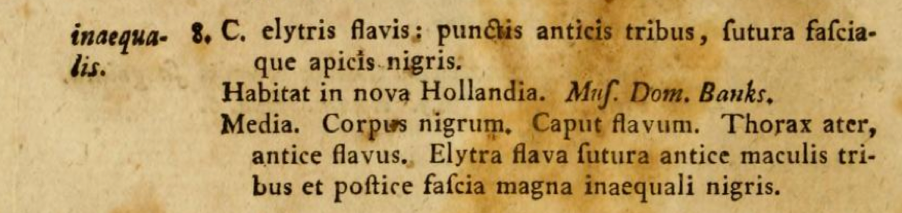

A type specimen is the original specimen from which species description is based on. In this case, the type specimen is labelled under the basionym (the original name the species was described under) Coccinella inaequalis, is a lectotype (an individual selected to be the type specimen from a series of other individuals of the same species known as syntypes) of a female individual. It is currently situated at the British Museum of Natural History. There does not seem to be an image of the specimen.[44]First Description

Coelophora inaequalis was first described by Danish zoologist Johan Christian Fabricius in his book Systema Entomologiae in 1775, under the genus Coccinella[45] . The species was identified in New Holland, which is the old name for Australia. |

| (28) |

Synonyms

According to the rules in the binomial nomenclature system of naming, all species should only have one name, consisting of the genus and the species epithet. However, different names are often given to the same species. This could be a result of the species being transferred to a different genus after it was first described, or a scientist mistaking it as a new species and describing it, even though it has already been described. The latter often occurs with regards to particularly wide ranging species. These alternative names are hence known as synonyms.Coelophora inaequalis has a pretty long list of synonyms, as shown below. This is likely due to the high level of intraspecific morphological variability, mentioned above under the polymorphism section. It is hence possible that scientists would misidentify different-looking individuals as new species. Additionally, its similarity to species under the genus Coccinella further adds to the confusion, and thus many synonyms were created under this genus name.

Coccinella inaequalis, Fabricius 1775 Coccinella novempunctata, Fabricius 1775 Coccinella novemmaculata, Fabricius, 1781 Coccinella circularis, Thunberg 1820 Coccinella religiosa, Lea 1902 Coelophora ripponi, Crotch 1874 Coelophora mastersi, Blackburn 1892 Coelophora veranioides, Blackburn 1894 Coelophora kochi, Weise 1913 Lemnia desolata, Mulsant 1850

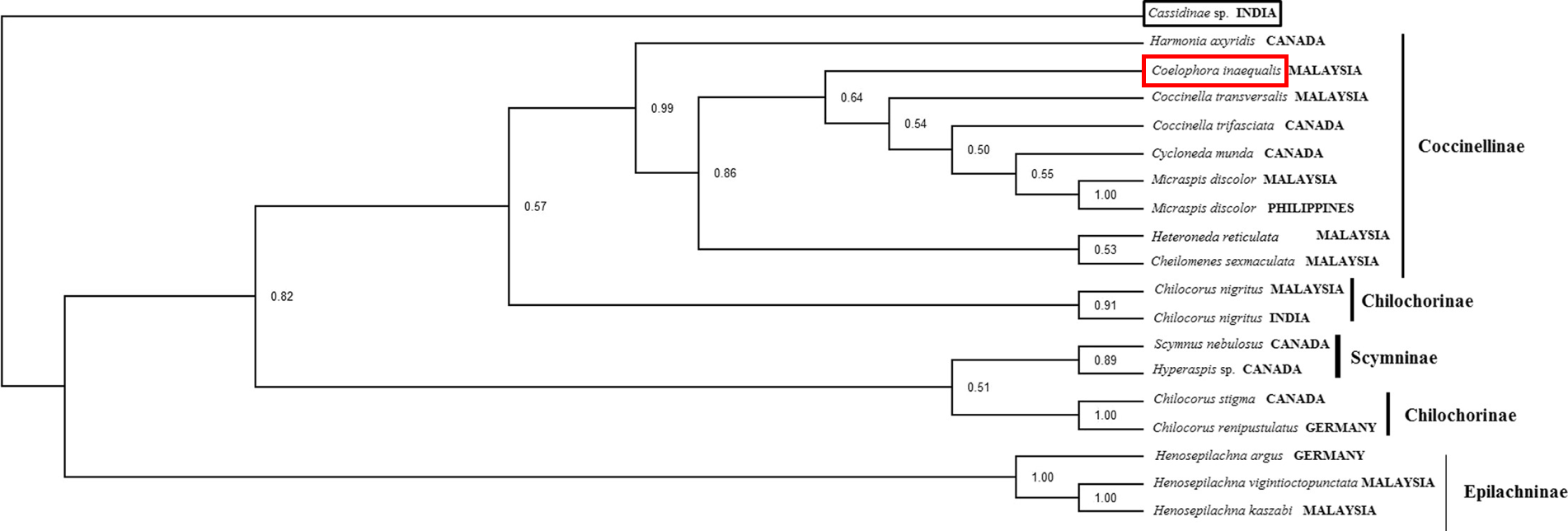

Phylogeny within the genus Coelophora

Coelophora is a small genus consisting of 30 species distributed in the Oriental, Pacific and Australian regions, and as of now has been relatively understudied. The composition of this genus has varied greatly over time, and its limits have often been disputed[46] . Fabricius first described the species under the genus Coccinella, until Mulsant transferred it to the genus Coelophora in 1850[47] . A phylogenetic study that included C. inaequalis was carried out using specimens collected from Malaysia. Specimens were barcoded using cytochrome oxidase I (COI), and some specimens were successfully morphologically identified to species level. Phylogenetic trees were constructed using Neighbour-Joining analysis, Maximum Parsimony (MP) and Bayesian Inference (BI) analysis. The tree pictured below using BI analysis supports the split of C. inaequalis from the genus Coccinella. Despite the low Posterior Probability (PP) value of 0.64, Coccinella appears to be a monophyletic group, separate from C. inaequalis. |

| (29) Consensus tree constructed using Bayesian Inference Analysis, with Posterior Probability values at the nodes. Image by Halim et al. (Fair use) |

As of now, however, there are still disagreements with regards to the boundaries of the genus. Majority of taxonomists have synonymized the genus Lemnia with Coelophora. Most have also acknowledged another genus Phrynocaria as separate. Nevertheless there are those that opt for the lesser beaten path; Sasaji (1982) still recognizes all three as separate genera, while Iablokoff-Khnzorian (1982), in a dramatic action, reduced the genus Coelophora to its type species C. inaequalis only[48] . Unfortunately, there does not seem to be any tree constructed of the genus Coelophora thus far, indicating that there is much to be done regarding its phylogeny.

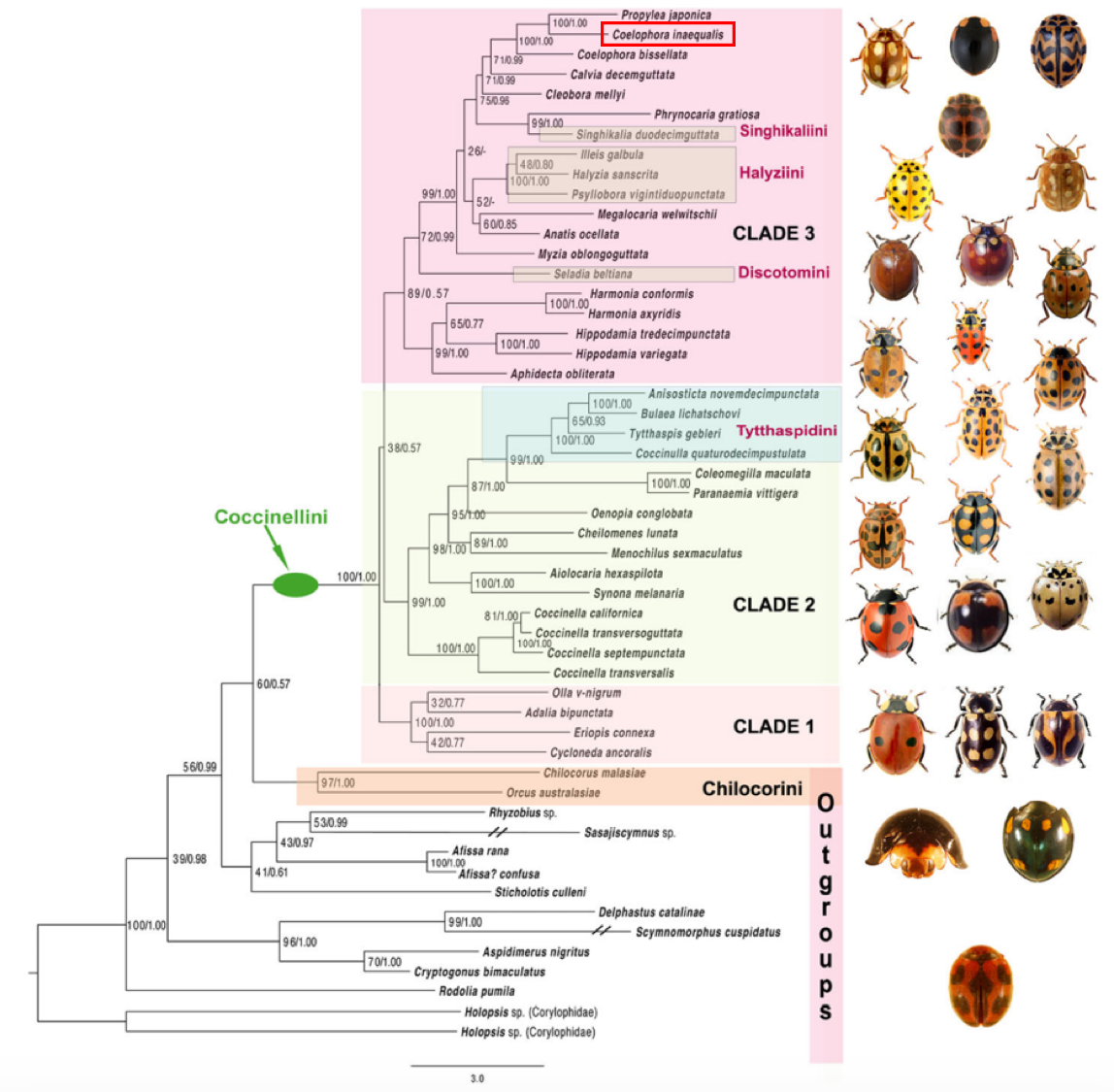

Phylogeny within the tribe Coccinellini

The tribe Coccinellini which contains Coelophora inaequalis, is commonly referred to as the ‘true ladybirds’, and consists of 90 genera with over 1000 species[49] . The tribe is well studied due to the charisma of many of the species as well as their relative economic importance as biological control agents. Despite this, the phylogeny and evolutionary history of the tribe is not well known, and extremely few phylogenetic trees that include C. inaequalis have been constructed. Escalona et al. have hence recently presented the most comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of Coccinellini that includes C. inaequalis thus far.Six morphological characters – adult pubescence (maturation), female colleterial glands (organs associated with the female genitals), larval dorsal gland openings, larval wax secretions and pupal gin traps (jaw-like pinching structures found on the pupa to defend from enemies) – were used in the phylogenetic analysis. Additionally, four nuclear and one mitochondrial gene fragments were used – two sections of carbamoylphosphate synthetase / aspartate transcarbamylase / dihydroorotase (CAD: CADMC and CADXM), topoisomerase I (TOPO), wingless (WGL), and cytochrome oxidase I (COI).

PCR products were sequenced using Sanger sequencing technology, and raw reads were assembled using Geneious. Manual checks for any sequencing errors, and manual edits were then carried out. The tree was then constructed using BI analysis and Maximum Likelihood. 1080 heuristic tree searches were carried out and the tree with the highest likelihood score selected. Bootstrap values were used to measure branch support.

|

| (30) Phylogeny of Coccinellini based on ML best topology. Numbers on branch nodes show bootstrap and posterior probability values above 0.5. Coelophora inaequalis is shown at the very top of the tree. Image by Escalona et al. (Fair use) |

Tribal classifications within the subfamily Coccinellinae have been unstable till now. The findings from this study showed that the monophyly of the tribe Coccinellini was strongly supported with bootstrap value of 100 and PP of 1.0. The tribe was found to be sister to the monophyletic group Chilocorini, and despite the low bootstrap value of 60 and PP of 0.57, this was consistent with previous studies.

Phylogenetic analysis has managed to recover three strongly supported, previously differently assigned clades within the tribe. However, the relationships between these clades are unresolved due to low support values. Coelophora inaequalis is found to be deeply nested within Clade 3, which consists of very poorly defined Old World genera. Interestingly, the genus Coelophora here does not seem to be monophyletic, as C. inaequalis is most closely related to a species from another genus, Propylea japonica (high bootstrap and PP at 100 and 1.0 respectively), instead of C. bissellata. Below is an image comparison between P. japonica and C. bissellata. The genus Propylea consists of 4 species, and its phylogeny seems quite understudied thus far[50] . Hence little supporting evidence aside from the reconstructed tree above can be found to tie the species and C. inaequalis together.

|

| (31) Left: Propylea japonica, image by P. Bailey from iNaturalist.org (Creative Commons. Right: Coelophora bissellata, image by 57Andrew from Flickr (permission pending) |

The molecular markers used in phylogenetic analysis are known to affect the tree results obtained. The study above utilized four nuclear genes and one mitochondrial. One way perhaps, to retrieve more information or confirmation on the relationships within the tree, especially that between C. inaequalis and P. japonica, could be to use other mitochondrial genes. Genes such as mitochondrial 12S or cytochrome-b, the latter which has proven useful in resolving relationships between closely-related taxa[51] .

- ^ “Coccinellidae,” by EOL. Encyclopedia of Life, n.d. URL: http://eol.org/pages/7459/overview (accessed on 10 Oct 2017)

- ^ “Pretty ladybirds are disease-ridden cannibals,” by H. Nicholls. BBC, 6 May 2015. URL:http://www.bbc.com/earth/story/20150506-the-truth-about-ladybirds (accessed 11 Oct 2017)

- ^ “A Love Affair With Ladybirds,” by S. Yap. MyGreenSpace, 2013. URL: https://www.nparks.gov.sg/mygreenspace/issue-19-vol-4-2013/conservation/a-love-affair-with-ladybirds (accessed 22 Oct 2017)

- ^ Frank, J. H. & Mizell R. F., (2014). Ladybirds, Ladybird beetles, Lady beetles, Ladybugs of Florida, Coeleoptera: Coccinellidae. University of Florida.

- ^ “Ladybirds, ladybugs and… cows?” by S. Thomas. Oxford Dictionaries, 24 June 2014. URL:http://blog.oxforddictionaries.com/2014/06/ladybirds-ladybugs-cows/ (accessed 13 Oct 2017)

- ^ “The fascinating reason why ladybugs are called that,” by K. Smallwood. Today I Found Out, 8 April 2015. URL: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2015/04/ladybugs-called/ (accessed 12 Oct 2017)

- ^ "Are all ladybugs ladies?". Animals.mom.me, n.d. URL: http://animals.mom.me/ladybugs-ladies-10807.html (accessed 12 Nov 2017)

- ^ “The fascinating reason why ladybugs are called that,” by K. Smallwood. Today I Found Out, 8 April 2015. URL: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2015/04/ladybugs-called/ (accessed 12 Oct 2017)

- ^ “inaequalis,”. Latin Dictionary. URL: http://www.latin-dictionary.org/Latin-English-Dictionary/inaequalis (accessed 17 Oct 2017)

- ^ Slipinski, A., 2013. Australian Ladybird Beetles (Coeleoptera: Coccinellidae): Their Biology and Classification. Csiro Publishing.

- ^ Chapin, E. A., 1965. Insects of Micronesia, 16(5).

- ^ Houston, K. J. & D. F. Hales, 1980. Allelic Frequencies and Inheritance of Colour Pattern in Coelophora inaequlis (F.) (Coeleoptera: Coccinellidae). Australian Journal of Zoology, 28(6): 669-677.

- ^ Houston, K. J. & D. F. Hales, 1980. Allelic Frequencies and Inheritance of Colour Pattern in Coelophora inaequlis (F.) (Coeleoptera: Coccinellidae). Australian Journal of Zoology, 28(6): 669-677

- ^ Chapin, E. A., 1965. Insects of Micronesia, Coleoptera: Coccinellidae. Insects of Micronesia, 16(5).

- ^ “Variable Ladybird – Coelophora inaequalis” by N. A. Martin. New Zealand Arthropod Collection Factsheet Series, 2016. URL: http://nzacfactsheets.landcareresearch.co.nz/factsheet/InterestingInsects/Variable-ladybird---Coelophora-inaequalis.html#natural enemies

- ^ Nicholson A. H., 2012. A new Coccinellid (Coeleoptera) record for New Zealand. New Zealand Entomologist, 79-81.

- ^ Mora, J. G., 1993. Life history and voracity of Coelophora inaequalis (Fabricius) (Coccinellidae: Coeloptera) on Aphis craccivora (Aphididae: Homoptera). Agris.

- ^ “A Love Affair With Ladybirds,” by S. Yap. MyGreenSpace, 2013. URL: https://www.nparks.gov.sg/mygreenspace/issue-19-vol-4-2013/conservation/a-love-affair-with-ladybirds (accessed 22 Oct 2017)

- ^ Frank, J. H. & Mizell R. F., (2014). Ladybirds, Ladybird beetles, Lady beetles, Ladybugs of Florida, Coeleoptera: Coccinellidae. University of Florida.

- ^ Fisher, T. W. et al., 1999. Handbook of Biological Control: Principles and Applications of Biological Control. Technology and Engineering

- ^ Houston K. J., 1988. Larvae of Coelophora inaequalis (F.), Phrynocaria gratiosa (Mulsant) and P. astrolabiana (Weise) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) with notes on their relationships and prey records. Journal of Australian Entomology, 27:199-211.

- ^ Frank, J. H. & Mizell R. F., (2014). Ladybirds, Ladybird beetles, Lady beetles, Ladybugs of Florida, Coeleoptera: Coccinellidae. University of Florida.

- ^ Riddick, E. W., 2017. Identification of conditions for successful aphid control by ladybirds in greenhouses. Insects, 8(2):38.

- ^ Ng, P. K. L., R. Corlett & H. T. W. Tan, (2011). Singapore Biodiversity: An Encyclopedia of the Natural Environment and Sustainable Development.

- ^ Frank, J. H. & Mizell R. F., (2014). Ladybirds, Ladybird beetles, Lady beetles, Ladybugs of Florida, Coeleoptera: Coccinellidae. University of Florida.

- ^ Riddick, E. W., 2017. Identification of conditions for successful aphid control by ladybirds in greenhouses. Insects, 8(2):38.

- ^ Imms, A. D., 1926. The biological control of insect pests and injurious plants in the Hawaiian islands. Annals of Applied Biology, 13(3): 402-423

- ^ Bishop, A. L. & P. R. B. Blood, 1978. Temporal distribution and adbundance of the Coccinellid complex as related to aphid populations on cotton in South-east Queensland. Australian Journal of Zoology, 26:153-158.

- ^ Hemptinne, J-L, G. Lognay, M. Doumbia & A. F. G. Dixon, 2001. Chemical nature and persistence of the oviposition deterring pheromone in the tracks of the larvae of the two spot ladybird, Adalia bipunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Chemoecology, 11(1):43-47.

- ^ Roy, H. E., H. Rudge, L. Goldrick & D. Hawkins, 2007. Eat of be eaten: prevalence and impact of egg cannibalism on two-spot ladybirds, Adalia bipunctata. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata, 125(1): 33-38.

- ^ Hemptinne, J-L, G. Lognay, M. Doumbia & A. F. G. Dixon, 2001. Chemical nature and persistence of the oviposition deterring pheromone in the tracks of the larvae of the two spot ladybird, Adalia bipunctata (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae). Chemoecology, 11(1):43-47.

- ^ Ceryngier, P, H. E. Roy & R. L. Poland, 2012. Natural Enemies of Ladybird Beetles. Ecology and Behavior of the Ladybird Beetles (Coccinellidae).

- ^ Majerus, M. E. N., J. J. Sloggett & J-L Hemptinne, 2007. Interactions between ants and aphidophagous and coccidophagous ladybirds. Population Ecology, 49(1):15-17.

- ^ Ceryngier, P, H. E. Roy & R. L. Poland, 2012. Natural Enemies of Ladybird Beetles. Ecology and Behavior of the Ladybird Beetles (Coccinellidae).

- ^ Berkvens, N. et al., 2010. Dinocampus coccinellae as a parasitoid of the invasive ladybird Harmonia axyris in Europe. Biological control, 53(1): 92-99.

- ^ “Wasp virus turns ladybug into zombie babysitters” by N. Weiler. Science, 10 Feb 2015. URL: http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/02/wasp-virus-turns-ladybugs-zombie-babysitters (accessed 5 Nov 2017)

- ^ Ceryngier, P, H. E. Roy & R. L. Poland, 2012. Natural Enemies of Ladybird Beetles. Ecology and Behavior of the Ladybird Beetles (Coccinellidae).

- ^ Majerus, M. E. N., J. J. Sloggett & J-L Hemptinne, 2007. Interactions between ants and aphidophagous and coccidophagous ladybirds. Population Ecology, 49(1):15-17.

- ^ Majerus, M. E. N., J. J. Sloggett & J-L Hemptinne, 2007. Interactions between ants and aphidophagous and coccidophagous ladybirds. Population Ecology, 49(1):15-17.

- ^ Ceryngier, P, H. E. Roy & R. L. Poland, 2012. Natural Enemies of Ladybird Beetles. Ecology and Behavior of the Ladybird Beetles (Coccinellidae).

- ^ “The fascinating reason why ladybugs are called that,” by K. Smallwood. Today I Found Out, 8 April 2015. URL: http://www.todayifoundout.com/index.php/2015/04/ladybugs-called/ (accessed 12 Oct 2017)

- ^ “The horrible meanings behind nursery rhymes,” by M. Archbold. National Catholic Register. http://www.ncregister.com/blog/matthew-archbold/the-horrible-meanings-behind-nursery-rhymes (accessed 9 Nov 2017)

- ^ "Francis (A Bug's Life),". Wikia, n.d. URL: http://disney.wikia.com/wiki/Francis_(A_Bug%27s_Life) (accessed 3 Nov 2017)

- ^ Poorani, J., 2002. An annotated checklist of the Coccinellidae (Coleoptera) (excluding Epilachninae) of the Indian subregion.

- ^ Fabricius, J. C., 1745-1808. Systema entomologiae : sistens insectorvm classes, ordines, genera, species, adiectis synonymis, locis, descriptionibvs, observationibvs.

- ^ Slipinski, A., 2013. Australian Ladybird Beetles (Coeleoptera: Coccinellidae): Their Biology and Classification. Csiro Publishing.

- ^ Houston K. J., 1988. Larvae of Coelophora inaequalis (F.), Phrynocaria gratiosa (Mulsant) and P. astrolabiana (Weise) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) with notes on their relationships and prey records. Journal of Australian Entomology, 27:199-211.

- ^ Houston K. J., 1988. Larvae of Coelophora inaequalis (F.), Phrynocaria gratiosa (Mulsant) and P. astrolabiana (Weise) (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) with notes on their relationships and prey records. Journal of Australian Entomology, 27:199-211.

- ^ Escalona, H. E. et al., 2017. Molecular phylogeny reveals food plasticity in the evolution of true ladybird beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae: Coccinellini). BMC Evolutionary Biology, 17(151)

- ^ Pervez, A. & O. Omkar, 2011. Ecology of aphidophagous ladybird Propylea species: A review. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, 14(3): 357-365

- ^ Patwardhan, A., S. Ray & A. Roy, 2014. Molecular markers in phylogenetic studies - A review. Journal of Phylogenetics and Evolutionary Biology, 2(2)